The story of civilization is written in the mud between the bay water and the plank road, and the tide was on the flood but not there yet. The wind and the spattering rain made arcing, graceful sweeps onto the black water; sagging triangles of foundering sails, seams of current like spilled rigging. And if I opened a window the smell would come wetly into the room and with it all the riotous sounds of the street and the docks. Rotten visitor, dead fish on the boiler, soggy dog. Mine was a king’s terrace, bay window overlooking the bay, imagined bretèche. No, not as safe as that. I was a pine marten stranded midriver during the flush.

Across the street, market day on the wharf. Women hauled their children among the vendors, bought fish and new potatoes, sacks of coarse flour, careful always to veer away from the drunken loggers and shoreshocked sailors, crippled beggars and instrumented buskers: ignorant conscripts all. A few boys with serious faces were stickfishing among the pilings, rigged for sturgeon but undersized to haul one in. Westward, the ships were three deep at the docks, loaded to their scuppers with lumber; brigs and barks, steamships too. Latecomers were anchored outside, drawing slack, twisting and bowing lightly, impatient at their tethers. They’d come from all over the world to be here, followed the stars until the stars disappeared. Safe harbor, our Harbor, not so deep but wide and scrimmed by enough timber to choke every saw in the hemisphere. From the mudflats to the sea blite, from the tidal prairie to the dark woods. The cocoon was finally splitting open on this world: sails of ships, papilio.

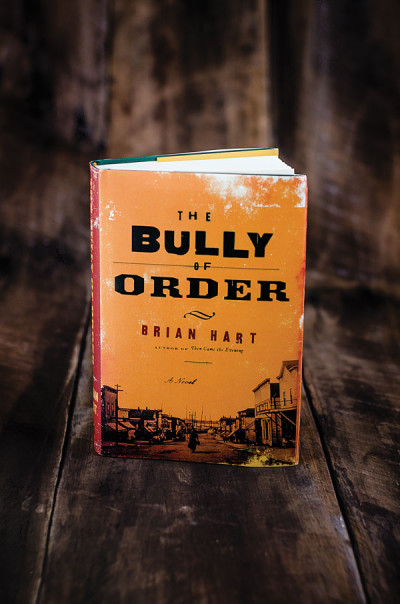

Brian Hart, author of “The Bully of Order” hadn’t planned to set his novel on Grays Harbor. “I was working on a short story set in the 1880s on the Salmon River in central Idaho about a guy building a sawmill,” Hart said. He researched how sawmills are made and their history, and that led to books and photographs from the Harbor.

“All of the sudden I was working on a book that takes place over there,” he said. “It was pretty much by accident.” He found a photograph of 12 men sitting on a section of tree they had cut down. “They’re sitting on this massive tree with their saws and I couldn’t get it out of my mind how much work it would take to cut it, move it and mill it,” Hart said. “That image carried me through.”

Hart was on a writing fellowship in Oysterville during the research and spent some time on the Harbor, but most of the research was done through libraries. “So much has changed on the Harbor in the last 100 years that it was hard to count on what I was seeing, compared to what I was writing,” he said.