In the early years, this was the entrance to Cohassett Beach.

If you visit Westport, you might happen upon a carved wooden sign marking the entrance to a tiny residential enclave called Cohasset Beach (with one t). But once upon a time, a local columnist chronicled big doings in the somewhat larger community of Cohassett Beach (with two t’s).

A Google Maps search of that name shows an area comprising about one-third of today’s Westport, spanning the area from State Route 105 north to approximately Lila Avenue. And yet a researcher would be hard-pressed to locate anything other than a passing mention of it online or in local histories.

Ruth McCausland’s book “Washington’s Westport” is a rare and excellent source of the area’s historical information. But for a deeper dive into the local culture, especially during the war years, there’s only one readily available choice.

“Cohassett Beach Chronicles” is a selection of writings by Kathy Hogan, who penned a regular column called “The Kitchen Critic” in the 1940s for the Grays Harbor Post in Aberdeen. Each week, she shared her witty observations of daily life in Cohassett Beach, from fish to fog to wayward dogs.

Just a few months after she started writing, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. In the blink of an eye, everything in Hogan’s world changed.

And so, from 1941 to 1945, her column provided a frank insider’s view of how her quiet coastal community reacted and adapted to its occupation by the 44th Infantry Division of the New Jersey National Guard — mostly very young men from New York and New Jersey charged with protecting the mainland from potential threats from the sea.

A number of our citizens have stood on their dunes during the past weeks and seen Japanese submarines attempt to throw monkey wrenches into west coast shipping. They have seen our ships attacked, and they have seen the attacks repulsed — and they have gone home and milked their cows, scolded their wives, and turned on their radios. Is that hysteria? (From “Hysterics—Beans,” Jan. 17, 1942)

This photo of Kathy Hogan in her later years was provided by Lucy Hart.

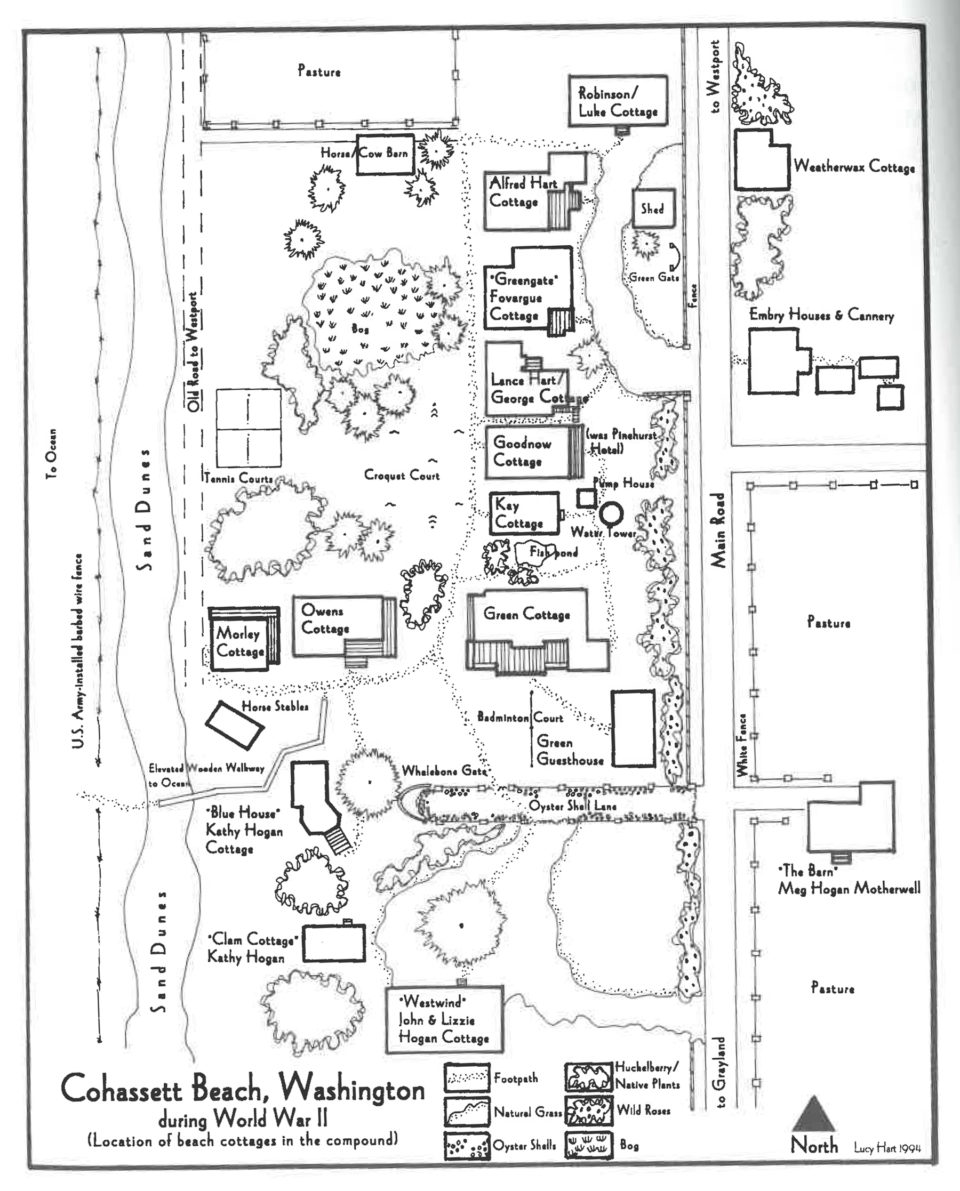

Co-editor Lucy Hart drew several pencil illustrations for the book, including this map of the Cohassett Beach compound during the war. The “Main Road” is called Forrest Street today.

The neighbors are busy filling galvanized wash tubs, old wash boilers, and scrub pails with Himalaya [black]berries, which are ripening now in the small clearings along the road and beyond the pasture. At least the men neighbors are busy. Their preoccupation amounts to feverish activity. [They] are acutely aware of impending famine at the village pub where one bottle of orange gin stands in lonely splendor on a once populous shelf, like an austere headland above an unfriendly sea. … Wine produced in sunspot years, says this week’s New Yorker magazine, is noticeably better than other vintages.

– From “Sea Changes,” Sept. 4, 1943

Co-editor Lucy Hart’s current home in Seattle is resplendent with colorful creations by friends and family members. At lower right is a picture of her long-ago Cohassett home sketched in 1925 by her father, famed artist Lance Wood Hart.

It’s a chunk of local history that might have been lost if not for the efforts of two women with childhood memories of that place and time: Klancy Clark de Nevers and Lucy Hart.

De Nevers’ father, Kearny Clark, was Hogan’s employer as editor of the Grays Harbor Post in Aberdeen. Today, she’s in her 80s and lives in Salt Lake City.

Hart lived in Eugene, Oregon, in the 1940s; but her great-aunt owned the Pinehurst Hotel in Cohassett Beach, and as a girl she spent two weeks there every summer. Now, at age 80, she resides in Seattle.

“Kathy Hogan was a legendary figure in my childhood. Stories about Kathy and her yarns were part of my family’s dinner table conversation,” says de Nevers. “My parents would visit her quaint beach cottage and come away cheered. We children held her in awe; we were not invited to join those visits.”

During the war years, Hogan painted a vivid and personal picture of the goings-on as her neighbors accommodated the young soldiers brought in from the East Coast; planted Victory Gardens, with varying results; and dealt in their own ways with the rationing of meat and shortages of alcohol.

Cohassett Beach hosted the

44th Infantry Division of the

New Jersey National Guard

during World War II.

“The U.S. Army brought in these boys and asked if they could live in our cottages. They were principally summer cottages, though Kathy lived there year-round,” says Hart. “These boys, being from big cities, didn’t know how to go out and chop wood for the fireplaces; so they’d break up furniture. They chopped up my sister’s wooden rocking horse that she adored, and burned it. But what did they know?”

Not long after Hogan retired, Kearney and Dorothy Clark gave her the bound volumes of the Grays Harbor Post from the years that held her columns (roughly 1940 to 1951), with the idea that she could publish a book of her writings.

“She had started looking through them and putting little colored slips of paper in different issues,” says de Nevers. “But she had no idea how to go about it, and she worried that her house would burn down. … So she gave them back to my parents and said: ‘I can’t do it.’”

But they refused to let the idea die.

“My mother gave me a manila envelope of about 20 columns of ‘The Kitchen Critic,’ which I had really never read, and I took them on a vacation when my husband and I were going camping around about Rainier and out to the coast,” says de Nevers. “So one day in a campground somewhere near Rainier, I sat reading these columns. And they were so enchanting that it just occurred to me that we should do something.”

And so she did.

“Klancy contacted me and asked if I would be interested in helping her put a book together,” says Hart. “I said, ‘I’d love to do it!’ It would be a labor of love, because I thought Kathy’s work was wonderful.”

They worked on it together for a couple of years, mostly by telephone.

“In ’95, the most advanced computer I had was a Radio Shack TRS-80; I’m not even sure I had internet,” says Hart. “The fact that Klancy could find a person to scan the articles to convert them into word processing files saved a ton of work.”

From left, Kristine Clark and Barbara Jean Sudderth play with a neighbor girl and her brother outside the Barn. In the background, in the steps, is Kathy Clark. (Info provided by Klancy Clark de Nevers)

De Nevers says, “We found a woman who trimmed them and scanned them with a digital scanner, which had only about 85% accuracy. Then she and her son edited them to correct them, and then I edited them again so they made sense. And that’s how we got the body of the book.”

Hart performed research at the courthouse in Montesano on who lived where in Cohassett; much of the info was on 3×5 cards, she says. With that information, she drew a map for the book to illustrate the town as it existed in the 1940s. She also searched the Seattle Post-Intelligencer photo archive for pictures to use in the book, and drew many other illustrations for the book.

They shopped a 45-page book proposal far and wide. Finally, it was Oregon State University Press that took it on — with a caveat.

Yesterday six soldiers carrying trench shovels rushed onto the beach and, facing each other, began to dig furiously. In a matter of seconds, they had made a hole big enough to bury an ox in. They bent over and examined the hole for an instant and then jumped to a new position. Again they dug furiously. The results were apparently unsatisfactory. They sprang to a third position, clenched their teeth with determination, and dug another ox’s grave. I kept on with my walk. … I used to stop and show our new soldiers how to dig razor clams. But this is getting to be an awfully big army.

– From “Cranberries and Clams,” July 4, 1942

“They said, ‘Yes, we would like to do this, but we don’t like the way you’ve proposed to organize the columns,’” says de Nevers. “So we got together and came up with the order the book is in now, which is sequential during the years of the war.” (It was originally organized by topic.)

They also added chronologies in the margins of the book to give historical context to Hogan’s writing. That information was taken from the Grays Harbor Post, de Nevers says. “At the end of the year, they’d publish a syndicated year-end summary — and it has historical errors, which of course we’ve been told.”

The old friends enjoyed working together on the project. Hart says they sometimes disagreed on certain aspects because she was an artist and de Nevers was a mathematician; but one thing they agreed on wholeheartedly was keeping Hogan’s writings intact.

“We said from the very beginning we weren’t going to be revisionist historians; there was no point,” says Hart. “She used terms that would be socially and culturally unacceptable now, but somebody should know that’s what people said in those days. We did not edit her work.”

Thanks in part to an enthusiastic review by Scott Simon on NPR, the original hardcover edition sold out quickly. OSU Press then printed several thousand copies in paperback. “Cohassett Beach Chronicles: World War II in the Pacific Northwest” can still be ordered through bookstores or online.

“The whole thing is a labor of love for a place that we loved and people that we loved,” says de Nevers.

Her favorite article in the book is the very last one, which was originally published Aug. 18, 1945 — just days after V-J Day. “What she wrote at the end of the war was very touching,” de Nevers says. “It’s hard to read, because I lost two uncles in that war. But I did like the last line in the book.”

“One thing I DO know,” I said, “I’ve graduated from the longest, toughest geography lesson in history.”