For decades, the 92-year-old, two-story mansion just east of Hoquiam’s Riverside Bridge was known as the “community’s attic.”

The shingle-sided Colonial Revival-style house fell into city hands as a gift in 1976, ending a search for a building to house a museum. In November of that year, it became the designated organization for Grays Harbor County history.

Now known as the Polson Museum — named after Arnold Polson, who commissioned the home’s construction in 1924 and lived there until the mid ’60s — the mansion with its towering white columns is a go-to assemblage of Grays Harbor artifacts. An artifact itself, the building houses an inventory spanning centuries of the area’s logging heritage and gives glimpses of everyday life from decades past.

But it wasn’t always as organized.

“I think anybody would tell you that the Polson in those days — and I’m talking about in the ’80s — was somewhat of the community’s attic,” said museum Director John Larson, a University of Chicago-educated historian. “It was a jumble of a lot of old stuff throughout.”

Nowadays, all 26 rooms inside the Polson serve a purpose, and no one who spends an afternoon there is likely to find anything resembling an attic.

Fit for a lumber baron

A century ago, the Polson name carried a lot of weight on Grays Harbor. Brothers Robert and Alex were among the Harbor’s first lumber barons, heading up the Polson Logging Company.

Robert paid to have the house built for Arnold, his nephew and Alex’s son, who had just married. Arthur Loveless, a prominent early-century Seattle architect, designed the house for Arnold and Priscilla Polson, giving it its iconic arches above the windows and columns that support the portico.

Inside, the house boasts 6,500 square feet, and the Polsons cut no corners on its construction — the house was built to their specifications from top to bottom.

Larson pointed to the 2 1/4-inch-wide floorboards in the 30-foot-long living room just left of the front door. The hemlock boards run the width of the building, front to back, single boards measuring 40 feet long in some parts of the house. The single-length boards eliminate end-joints, Larson said, which make for little creaking.

Such specifications required the boards be milled at the Eureka Lumber Company, a Polson-owned mill that once sat at the foot of Ontario Street in Hoquiam.

“A lot of people come here also to see this old house,” Larson said, in addition to what’s inside. “They can walk through the entire house and kind of experience what life in a big mansion like this might have been like.”

Arnold and Priscilla Polson left the house and put it up for sale in 1965. For years it sat empty, with prospective buyers arguing that it was too much work for the price, or too expensive altogether.

The house was under Priscilla’s care after Arnold died in 1968. A woman who associated more with life in Seattle, she had no reason to stay in Hoquiam, Larson said.

By 1976, officials and citizens interested in bringing a museum to the area had identified the Polson property as an ideal site. Riverside Avenue, five years earlier, had been converted to its current one-way, westbound configuration. With the mansion unoccupied for the last decade, it had become a blight.

Priscilla Polson eventually donated the house to the City of Hoquiam. The city owns the building to this day, but the Polson Museum, a registered non-profit organization, was founded to operate it in November 1976.

“Our mission is much broader than just simply Polson history or logging history,” Larson added. “You come in here and you’re going to experience a wide variety of topics.”

(Kyle Mittan | The Daily World)

Polson Museum Director John Larson sits on the running board of the Polson No. 45, a logging locomotive that once transported logs around the Harbor in the early-to-mid 1900s.

‘Something for everybody’

Beyond the columns and the 10 steps leading up to the front door, the Polson’s first-floor entryway leaves the visitor with a few choices. A left turn into the 30-foot-long living room leads to an exhibit featuring local photography, which rotates seasonally. Hang a right, and you’ll find yourself in a former dining room that showcase Native American basketry.

Straight ahead to the right is the museum’s research library, a den-like corner room with a player piano and volumes of reference materials, including Hoquiam High School annuals and city directories dating back more than a century.

The museum has no designated route, and it’s like that on purpose, Larson said.

“We expect our visitors to find what interests them and what captures their attention and love,” he said. “There’s certainly something for everybody here, from those who are interested in heavy-duty industrial history to those that are interested in fine clothing of bygone years.”

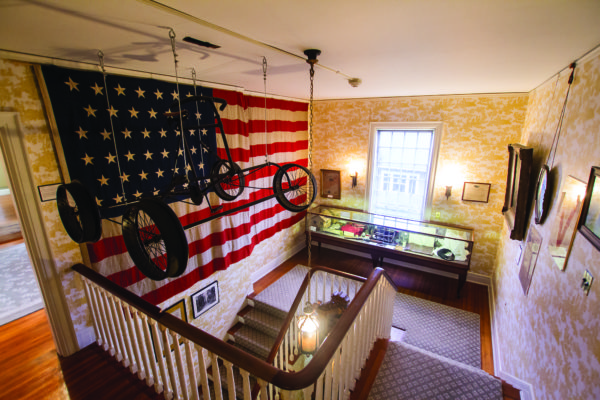

A slight left from the entrance takes the visitor up two flights of stairs to the second floor, where the bulk of the museum’s logging and sawmilling exhibits are kept. A 160 square-foot model train exhibit depicts a logging railyard circa 1915. Logging tools spanning the eras of technological advancement surround the display.

The adjacent room features a sawmilling exhibit, complete with the various sawblades once used to get the job done. The room’s focal point — a neon sign sporting the number 405 — also showcase a darker side of Harbor history. The 405, once located at 405 E. State Street in Aberdeen, was known as one of the area’s classier brothels, and one of the last to close in 1964.

But the museum’s Holy Grail of logging artifacts isn’t anywhere inside the house — it wouldn’t fit.

The wooden shed at the east end of the lot houses the No. 45 steam-powered locomotive that once carried logs for the Polson Logging Company in the early-to-mid 1900s — 45 tons of logging history.

The massive wooden shop was built relatively recently, but it might as well be straight from an early-1900’s logging camp, complete with a short set of railroad tracks and all the classic machinery and tools one would find at such a site. The shop was built in 2009, Larson said, back when the museum had no locomotive, but hoped to get one.

Six years later, with the help of Tim and Lisa Quigg, benefactors with local ties, the museum was able to buy the engine from a collector in Oregon. Getting the No. 45 back to the Harbor was a major development, Larson said, considering all logging locomotives that once served the Harbor have since left the area.

“Every one of them was sold, given away, scrapped — they’ve been dispersed around the country,” Larson said. “So for us at the Polson to actually bring that back was a big deal.”

The locomotive is currently undergoing a restoration process, led by a group of locomotive experts who volunteer their time for the effort.

As significant as the No. 45’s arrival to the Harbor was, Larson is quick to emphasize that it’s not the only artifact in the logging camp exhibit. The back end of the shop is home to a Lamb SpeedTrak, a massive piece of machinery that carried large old-growth logs. A 25-foot-long, 28,000-pound log, harvested by Rayonier near Copalis Crossing, now sits atop the SpeedTrak, displaying the machine’s functionality.

“Some of those artifacts are, historically, just as important as the locomotive,” Larson said.

(Gabe Green | The Daily World)

Future plans

Even with an entire mansion and replica logging camp full of artifacts, Larson said he has plans for expansion and changes to existing exhibits.

Pointing to the museum’s clothing exhibits as an example, Larson said he would like to see the garments in that collection displayed in a way that better portrays how they were used, rather than how they look packed into closets.

Larson said he would also like to see the house itself featured more.

The museum’s expanding, too. In late December, it completed the purchase of the Japanesque craftsman bungalow just west of the Polson lot, and fourplex west of that. The house, to be named the Hubble House after the family that built it in 1915, will offer additional storage, exhibit and community-event space, as well as a woodshop in the garage for restoration and other projects.

But until then, the Polson’s 26 rooms — and an entire logging camp — have plenty to offer for anyone hoping to get a taste of Grays Harbor’s most iconic industries, and the people who helped lead them.